ladanum video 1

ladanum video2

ladanum video 3

Saturday, November 18, 2006

ladanum(ledanum) in Herodotus-Thalia

of no other animal. You find in a hare's belly, at one and the same

time, some of the young all covered with fur, others quite naked,

others again just fully formed in the womb, while the hare perhaps has

lately conceived afresh. The lioness, on the other hand, which is

one of the strongest and boldest of brutes, brings forth young but

once in her lifetime, and then a single cub; she cannot possibly

conceive again, since she loses her womb at the same time that she

drops her young. The reason of this is that as soon as the cub

begins to stir inside the dam, his claws, which are sharper than those

of any other animal, scratch the womb; as the time goes on, and he

grows bigger, he tears it ever more and more; so that at last, when

the birth comes, there is not a morsel in the whole womb that is

sound.

Now with respect to the vipers and the winged snakes of Arabia, if

they increased as fast as their nature would allow, impossible were it

for man to maintain himself upon the earth. Accordingly it is found

that when the male and female come together, at the very moment of

impregnation, the female seizes the male by the neck, and having

once fastened, cannot be brought to leave go till she has bit the neck

entirely through. And so the male perishes; but after a while he is

revenged upon the female by means of the young, which, while still

unborn, gnaw a passage through the womb, and then through the belly of

their mother, and so make their entrance into the world. Contrariwise,

other snakes, which are harmless, lay eggs, and hatch a vast number of

young. Vipers are found in all parts of the world, but the winged

serpents are nowhere seen except in Arabia, where they are all

congregated together. This makes them appear so numerous.

Such, then, is the way in which the Arabians obtain their

frankincense; their manner of collecting the cassia is the following:-

They cover all their body and their face with the hides of oxen and

other skins, leaving only holes for the eyes, and thus protected go in

search of the cassia, which grows in a lake of no great depth. All

round the shores and in the lake itself there dwell a number of winged

animals, much resembling bats, which screech horribly, and are very

valiant. These creatures they must keep from their eyes all the

while that they gather the cassia.

Still more wonderful is the mode in which they collect the

cinnamon. Where the wood grows, and what country produces it, they

cannot tell- only some, following probability, relate that it comes

from the country in which Bacchus was brought up. Great birds, they

say, bring the sticks which we Greeks, taking the word from the

Phoenicians, call cinnamon, and carry them up into the air to make

their nests. These are fastened with a sort of mud to a sheer face

of rock, where no foot of man is able to climb. So the Arabians, to

get the cinnamon, use the following artifice. They cut all the oxen

and asses and beasts of burthen that die in their land into large

pieces, which they carry with them into those regions, and Place

near the nests: then they withdraw to a distance, and the old birds,

swooping down, seize the pieces of meat and fly with them up to

their nests; which, not being able to support the weight, break off

and fall to the ground. Hereupon the Arabians return and collect the

cinnamon, which is afterwards carried from Arabia into other

countries.

Ledanum, which the Arabs call ladanum, is procured in a yet

stranger fashion. Found in a most inodorous place, it is the

sweetest-scented of all substances. It is gathered from the beards

of he-goats, where it is found sticking like gum, having come from the

bushes on which they browse. It is used in many sorts of unguents, and

is what the Arabs burn chiefly as incense.

Concerning the spices of Arabia let no more be said. The whole

country is scented with them, and exhales an odour marvellously sweet.

There are also in Arabia two kinds of sheep worthy of admiration,

the like of which is nowhere else to be seen; the one kind has long

tails, not less than three cubits in length, which, if they were

Laudanum (# than ladanum,labdanum)

From LoveToKnow 1911 : http://www.1911encyclopedia.org/Laudanum

LAUDANUM, originally the name given by Paracelsus to a famous medical preparation of his own composed of gold, pearls, &c. (Opera, 1658, i. 492/2), but containing opium as its chief ingredient. The term is now only used for the alcoholic tincture of opium (q.v.). The name was either invented by Paracelsus from Lat. laudare to praise, or was a corrupted form of "ladanum" (Gr. X 5avov, from Pers. ladan), a resinous juice or gum obtained from various kinds of the Cistus shrub, formerly used medicinally in external applications and as a stomachic, but now only in perfumery and in making fumigating pastilles, &c.

Perfumery and ladanum

Perfumery and ladanum

http://www.cistuspage.org.uk/perfumery.htm

In ancient times the valuable aromatic gum ladanum was gathered manually from Cistus creticus subsp. creticus, especially in Crete and Cyprus. The gum is exuded from glandular hairs on the leaves and young stems, especially under hot sunshine. It was gathered by allowing goats to graze on and among the plants; the ladanum adhered to their beards, which were then cut off. Alternatively a device called a ladanisterion or ergastiri, with long thongs of leather, was drawn over the plants by hand during the hottest part of the day, when the ladanum was at its runniest and stickiest.. The leather thongs became caked with ladanum, which was then scraped off and formed into lumps of various shapes. A very small amount of ladanum is still gathered in this traditional way in a small area surrounding a village in northern Crete.

The modern perfume industry extracts its ladanum from a different species, Cistus ladanifer, whose leaves and young stems are covered with the very sticky gum. The industry is centred in Spain, close to the north-eastern corner of Portugal and a small area in southern France. Young stems are mechanically harvested from the plants and subjected to industrial processes to extract the gum and refine it in various ways.

Three main processes produce a) Oil of Ladanum, b) Concrete or Absolute of Ladanum and c) Labdanum Resinoid or Resinol.

Perfumers classify ladanum as an "amber" odour. It commands a very high price. It is rich, long-lasting and widely used as a fixative, as well as for its own fragrance.

N.B. There is no connection with laudanum!

ladanum in bible

LADANUM (CTAKTH [ADEFL], RESINA),

Gen. 37251 (

name of a resin called by the Arabs Lidhan or ladan‘

which was yielded by some species of Cistus. It was

known to the Greeks as early as the times of Herodotus

and Theophrastus by the names X+Sov, hdSuvov, and

h.?Suvor, which are very closely allied to the Arabic

name.

Ladanum is described by Herodotus (3 1x2) as particulaFly

fragrant, though gathered from the beards of goats, on which

it is found sticking ; similarly Dioscorides (1 128). Tournefort,

in modern times (Voyage, 129)) has given a detailed description

of the mode of obtaining ladanum. He relates that it is now

gathered by means of a Aasavronjpmv or kind of flail2 with

which the plants are threshed. When these thongs are

loaded with the fiagrant and sticky resin they are scraped

with a knife. the substance is then roiled into a mass,

in which state‘it is called ladanum or labdanum. Ladanum

consists of resin and volatile oil, and is highly fragrant, and

stimulant as a medicine but is often adulterated wlth sand in

commerce. The ladan& which is used in

chiefly in the Greek isles, and also in continental

is yielded by species of the genus Cistus (especially by C.

weticus) which are known in this country by the name of Rock

Rose ; they are natives of the S. of Europe, the

islands, and the N. of Africa. According to Tristram (FFP

235) Palestinian ladanum is derived from Cisfus villosus L.,

which grows ‘in the hill district; E. and W. of Jordan,’ ahd is

‘especially plentiful on

a varietyof this and distinguished by its yiscidity, is fthe

common formon the southern hdls.’ [Fonck thmks of the C~strrs

salv’uifoo(ius, which is also plentiful on

but H. Christ (ZDPV 65fi [1899]) questions this identification.]

Ladanum is said by Pliny. as it was long before said by

Herodotus, to be a product of

been proved to be the case in modern times. Enoi~gh,

however, has been adduced to show that Zadanum was

known to, and esteemed by, the ancients ; and, as it is

1 According to Moidtmann and Muller (Sub. Dfnk. 84) the

ZEdhan is the proper Arabic form derived from Persian.

2 Specimens of the implement can be seen in the Museum at

Kew (Crete and

Page 2692

stated to have been a product of

likely to have been sent to

as merchandise. The word Zridan is found in the inscription

on a S. Arabian censer (Sa6. Denk. 84). and

in Assyrian in the list of objects received as tribute from

Damascus byTiglath-Pileser 111. (KA TC2) 151, 18). The

biblical narrative (J) shows that was some precious

gum produced in Canaan or at least in

See Royle's article ' Lot' in Kitto's Bibl. Cycl., on which this

article is mainly based. N. M.-W. T. T.-

page 2963

http://www.case.edu/univlib/preserve/Etana/encyl_biblica_l-p/laadah-lazarus.pdf

Myrrh

Myrrh - Heb. mor.

(1.) First mentioned as a principal ingredient in the holy anointing oil (Ex. 30:23). It formed part of the gifts brought by the wise men from the east, who came to worship the infant Jesus (Matt. 2:11). It was used in embalming (John 19:39), also as a perfume (Esther 2:12; Ps. 45:8; Prov. 7:17). It was a custom of the Jews to give those who were condemned to death by crucifixion "wine mingled with myrrh" to produce insensibility. This drugged wine was probably partaken of by the two malefactors, but when the Roman soldiers pressed it upon Jesus "he received it not" (Mark 15:23). (See GALL .)

This was the gum or viscid white liquid which flows from a tree resembling the acacia, found in Africa and

(2.) Another word lot is also translated "myrrh" (Gen. 37:25; 43:11; R.V., marg., "or ladanum"). What was meant by this word is uncertain. It has been thought to be the chestnut, mastich, stacte, balsam, turpentine, pistachio nut, or the lotus. It is probably correctly rendered by the Latin word ladanum, the Arabic ladan, an aromatic juice of a shrub called the Cistus or rock rose, which has the same qualities, though in a slight degree, of opium, whence a decoction of opium is called laudanum. This plant was indigenous to

http://www.htmlbible.com/kjv30/easton/east2632.htm

Myrrh

NET Glossary: a reddish-brown resinous material, the dried sap of the myrrh tree, Commiphora myrrha or Balsamodendron, an ingredient of perfumes and incense highly prized in ancient times and often worth more than its weight in gold; myrrh was also used as an ingredient in embalming ointment

Myrrh [EBD]

Heb. mor. (1.) First mentioned as a principal ingredient in the holy anointing oil (Ex. 30:23). It formed part of the gifts brought by the wise men from the east, who came to worship the infant Jesus (Matt. 2:11). It was used in embalming (John 19:39), also as a perfume (Esther 2:12; Ps. 45:8; Prov. 7:17). It was a custom of the Jews to give those who were condemned to death by crucifixion "wine mingled with myrrh" to produce insensibility. This drugged wine was probably partaken of by the two malefactors, but when the Roman soldiers pressed it upon Jesus "he received it not" (Mark 15:23). (See GALL.)

This was the gum or viscid white liquid which flows from a tree resembling the acacia, found in Africa and

(2.) Another word lot is also translated "myrrh" (Gen. 37:25; 43:11; R.V., marg., "or ladanum"). What was meant by this word is uncertain. It has been thought to be the chestnut, mastich, stacte, balsam, turpentine, pistachio nut, or the lotus. It is probably correctly rendered by the Latin word ladanum, the Arabic ladan, an aromatic juice of a shrub called the Cistus or rock rose, which has the same qualities, though in a slight degree, of opium, whence a decoction of opium is called laudanum. This plant was indigenous to

Myrrh [NAVE]

MYRRH, a fragrant gum. A product of the

One of the compounds in the sacred anointing oil, Ex. 30:23.

Used as a perfume, Esth. 2:12; Psa. 45:8; Prov. 7:17; Song 3:6; 5:13.

Brought by wise men as a present to Jesus, Matt. 2:11.

Offered to Jesus on the cross, Mark 15:23.

Used for embalming, John 19:39.

Traffic in, Gen. 37:25; 43:11.

MYRRH [SMITH]

This substance is mentioned in (Exodus 30:23) as one of the ingredients of the "oil of holy ointment:" in (Esther 2:12) as one of the substances used in the purification of women; in (Psalms 45:8; Proverbs 7:17) and in several passages in Canticles, as a perfume. The Greek occurs in (Matthew 2:11) among the gifts brought by the wise men to the infant Jesus and in (Mark 15:23) it is said that "wine mingled with myrrh" was offered to but refused by, our Lord on the cross. Myrrh was also used for embalming. See John 19;39 and Herod. ii. 86. The Balsamodendron myrrha , which produces the myrrh of commerce, has a wood and bark which emit a strong odor; the gum which exudes from the bark is at first oily, but becomes hard by exposure to the air. (This myrrh is in small yellowish or white globules or tears. The tree is small, with a stunted trunk, covered with light-gray bark, It is found in Arabia Felix. The myrrh of (Genesis 37:25) was probably ladalzum , a highly-fragrant resin and volatile oil used as a cosmetic, and stimulative as a medicine. It is yielded by the cistus , known in Europe as the rock rose, a shrub with rose-colored flowers, growing in

MYRRH [ISBE]

MYRRH - mur:

(1) (mor or mowr; Arabic murr]): This substance is mentioned as valuable for its perfume (Ps 45:8; Prov 7:17; Song 3:6; 4:14), and as one of the constituents of the holy incense (Ex 30:23; see also Song 4:6; 5:1,5,13). Mor is generally identified with the "myrrh" of commerce, the dried gum of a species of balsam (Balsamodendron myrrha). This is a stunted tree growing in Arabia, having a light-gray bark; the gum resin exudes in small tear-like drops which dry to a rich brown or reddish-yellow, brittle substance, with a faint though agreeable smell and a warm, bitter taste. It is still used as medicine (Mk 15:23). On account, however, of the references to "flowing myrrh" (Ex 30:23) and "liquid myrrh" (Song 5:5,13), Schweinfurth maintains that mor was not a dried gum but the liquid balsam of Balsamodendron opobalsamum.

See BALSAM.

Whichever view is correct, it is probable that the smurna, of the New Testament was the same. In Mt 2:11 it is brought by the "Wise men" of the East as an offering to the infant Saviour; in Mk 15:23 it is offered mingled with wine as an anesthetic to the suffering Redeemer, and in Jn 19:39 a "mixture of myrrh and aloes" is brought by Nicodemus to embalm the sacred body.

(2) (loT, stakte; translated "myrrh" in Gen 37:25, margin "ladanum"; 43:11): The fragrant resin obtained from some species of cistus and called in Arabic ladham, in Latin ladanum. The cistus or "rock rose" is exceedingly common all over the mountains of

E. W. G. Masterman

http://net.bible.org/dictionary.php?word=Myrrh

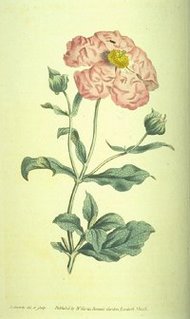

Ladanum (Cistus incanus L.)

“Take some of the choice fruits from the land, and carry them down as a present to the man—a little balm and a little honey, gum, myrrh, pistachio nuts and almonds”

The balm mentioned in Genesis is thought to be ladanum, a sturdy shrub that adorns the hills beside the

The Rockroses by Ken Montgomery

The Rockroses

by Ken Montgomery

I confess to a love affair with rockroses that

has lasted almost thirty years. These fascinating

and extraordinarily beautiful plants bring a long

list of desirable qualities to the world of

horticulture.

Most rockroses are extremely drought-tolerant.

Once established they require minimal irrigation in

the dry season and can contribute significantly to

water conservation efforts. Gernerally speaking,

these shrubs are cold-hardy to temperatures as low

as 5°F., adaptable to a wide range of soils and

microclimates, easy to grow and maintain and

resistant to serious pests and diseases. Many have

extensive root systems, making them useful in

stabilizing slopes and controlling soil erosion.

They provide cover for wildlife and are compatible

with [California] native vegitation. At the same

time, they are not invasive and pose a minimal

threat of spreading into natural areas and becoming

pests. Low-growing kinds are somewhat

fire-retardant and many others are unpalatable to

deer.

The common name "rockrose" referes most

often to the members of three closely related

genera - Cistus, Halimium, and Halimiocistus.

These groups are classified together in the family

Cistaceae along with sunroses (Helianthemum).

Rockroses are so called because their flowers

resemble single, old-fashioned roses (although

they are unrelated) and because they prefer to

grow in rocky, well-drained soil. They are

evergreen strongly woody shrubs, varying in

height from two to over eight feet and from three

to more than six feet across. Some sprawl on the

groun, while others are open, erect and rangy.

These are not plants for formal, highly structured

gardens. Even with moderate pruning, rosroses

have a wild, undomesticated look in the landscape.

They bloom most heavily in the spring, with some

species beginning as early as March. Each flower

lasts only a few hours but many kinds bloom so

profusely that the entire plant is covered with

hundred of new blossoms each day. Colors range

from white and many shades of pink and

lavender-pink in Cistus to white and yellow in

Halimium. Flowers of some rockroses also have a

showy red to maroon spot or blotch at the base of

each petal, offering stunning contrasts to the

numerous bright yellow stamens at the center.

All rockroses are native to lands surrounding

the Mediterranean Sea. They are adapted to long,

hot, dry summers - the same conditions found in

much of California. As we begin facing the reality

of a semi-arid Mediterranean climate here in

California, the use of appropriate plants in our

gardens and landscape takes on increasing

importance. In this context, rockroses are enjoying

greater popularity than ever before. Old faorites

are being rediscovered and many fine new

selections are being introduced into the nursery

trade. The future is bright for rockroses, and I

couldn't be happier!

Cistus creticus L.

Cistus creticus L.

Cistaceæ

Western & Central Mediterranean, from

Southern Spain to South-Eastern Italy - on

sandy soils and scrub

Pink Rockrose, Mauve Rockrose, Hairy

Rockrose, Gum Cistus, Grey Rockrose,

Hoary Cistus, Balm of Gilead (biblical)

Cisto rosso, Cisto villoso, Rosola

(Italian), Turdju burdu, Mudrju biancu,

Mucchju biancu, Murdegu oinu (Italian,

Sardo), Jara gris (Castillian Spanish)

A highly variable species which helps to

confuse identification of species and

natural hybrids. Overall, the foliage

tends to be somewhat sticky, slightly

undulate to very wavy edged and/or

crinkly in texture. The 4-5cm magenta

pink flowers are borne singly throughout

the plant from March to June. Found in

the garrigue and maquis, rocky areas,

stony dry hillsides, open pine forests.

Tolerant of a variety of substrate but

prefer calcareous soil.

Synonyms C. incanus C. polymorphus

Willk. C. villosus

Forms/Subspecies/Varieties

C. creticus forma albus white flowers

C. creticus subsp. corsicus

Cistus creticus - mediterranean climate gardening througho... http://www.mediterraneangardensociety.org/plants/Cistus....

2 of 2 29/11/2004 10:09 µµ

C. creticus subsp. creticus wavy-edged

leaves with sticky hairs, exuding ladanum

Cultivars/Selections

C. creticus 'Lasithi' compact habit,

rounded form

C. creticus forma albus 'Tania Compton'

an albino selection

This site is hosted

by

The Mediterranean

Garden Society

Concept/page design by Seán A. O'Hara,

independent of the Mediterranean Garden

Society.

All content © copyrighted by source or

author,

and not to be reproduced without

authorization.

Cistaceae by Olivier Filippi

Cistaceae

by Olivier Filippi

(translation by Sean A. O'Hara)

The flowering of the cistuses in the garrigue in spring remains one of the most beautiful spectacles of our Mediterranean landscape. The richness of the colours, the diversity their evergreen foliages and especially the robust habit of these plants makes the group quite versatile: free standing hedges for the tall varieties, large, massed groundcovers for those of medium height, mats and tumblers for low-growing or prostrate types.

All the cistuses are very drought tolerant. They prosper in good drainage. Their tolerance of akalinity and cold is specific for each variety (see the two tables below). La life expectancy of the cistuses is not very long: eight to ten years for the species, and up to fifteen years for the hybrids. The cistuses age better in difficult conditions: avoid rich soils, manure, water in summer. To increase to them life expectancy, it is good to cut them back lightly each year in the autumn for the mild winter regions or at the end of the winter for the colder regions.

It is possible to visit our "garden of rockroses" from April 15 through the end of May. There you will be able to study the flowers of all the species and hybrids presented below.

Olivier Filippi

Cistus creticus (Cistaceae) - Fragrant Rockrose

Fragrant Rockrose

http://www.mediterraneangardensociety.org/plants/Cistus

"Found throughout the Mediterranean region, this

extremely variable plant has gray-green, often

recirved leaves and hairy stems. Flowers range from

mid-pink to rose-purple or pale lilac. Some

botanical authorities list Cistus creticus as a

subspecies of Cistus incanus as they are closely

allied in form and flower." The Rockroses, by Kem

Montgomery

Cistus creticus 'John Catterson'

"A rockrose with exceptionally fine form, 'John

Catterson' originated as a chance seedling

discovered and introduced by Gary Ratway and

Deborah Whigham of Digging Dog Nursery. It is

excellent for coastal areas, offering 3-inch magent

flowers and a tight, mounding growth habit to 5 feet

tall and as wide. Blooming season on the

Mendocino coast if from March throught July."

The Rockroses, by Kem Montgomery

For further reading, see also:

Brooms and Rockroses: a gardener's

guide,

by Lester Hawkins,

Pacific Horticulture, Fall 1978,

(Cistus creticus featured on cover)

Balm of Gilead

http://web.odu.edu/webroot/instr/sci/plant.nsf/pages/cistus

Why There May Be No Balm in Gilead(1)

Balm of Gilead is an image familiar to Bible students even though it is mentioned in only

two verses. The weeping prophet, as Jeremiah is known, writes in Jeremiah 8:22, "Is there

no balm in Gilead? Is there no physician there? Why then is there no healing for the wound

of my people?" What is this product of Gilead?

First, what is Gilead? According to the biblical account in the book of Joshua(2), Gilead is

apparently the region from the middle of the Arnon Gorge (Wadi Mujib) to Mount Hermon

(Jebel Al Sheik) with the Jabbok River (Zarqa River) being the middle of the territory. This

included the domain of the Ammonites and the Amorites as well as the region known as

Bashan. In division of territory to the patriarchs, Gilead was apportioned to the half tribe of

Manasseh (the other half remained west of the Jordan River), Reuben, and Gad.

Although a small area in terms of square kilometers, Gilead is diverse stretching from the

margins of the Jordan valley and the peaks along the Rift Valley to the edge of the Badia

(steppe). In ancient times parts of Gilead were covered with forests. These forests were the

Balm of Gilead http://web.odu.edu/webroot/instr/sci/plant.nsf/pages/cistus

2 of 8 29/11/2004 10:16 µµ

southernmost extension of their kind, and the southern extreme of the range of the Aleppo

pine. Today, only vestiges of these forests remain. A prime example is Dibbeen National

Park.

At Dibbeen and scattered other remnants in the area, the forest is dominated by the Aleppo

pine. This tree is familiar to anyone who has visited Jordan because it is widely planted. It

probably only formed extensive forests, however, in areas with higher rainfall. Pines are the

dominant trees but oak (ballot), pistacia (buttim), and carob (kharrob) are also present.

A feature of the natural pine forest is a distinct stratification of the vegetation. The trees are

the upper layer. Much closer to the ground is a layer of shrubs, dominated by two species of

the genus Cistus. More on these later. Closer yet to the soil are numerous non-woody plants,

many of them in the legume family.

One of the characteristics of plants found in this vegetation type is the presence of essential

oils, literally oils that have an essence. Pine would fit this category as would numerous of

the understory shrubs. Some, like the legume Ononis, have sticky hairs. Others, like various

members of the mint family, lack the sticky hairs but contain oils that are evident when the

plant is crushed.

If the forest is degraded through heavy grazing, the oaks will predominate. This sort of

forest is evident in the hills north of Ajlon as at Istayfanah. Here, you will not see a distinct

stratification although the flora is rich and diverse. In the spring, the forest contains showy

plants such as orchids and anemones which are most common at the margins where more

light is available.

For me, the most desirable time to visit Dibbeen is in the late spring in the afternoon. Shrubs

are still green, some flowers of Cistus are present. After the hot day, resin is obvious on the

plants. Pine leaves, Cistus, and various native mints combine to give a sweet fragrance. The

long rays of the sun in the late afternoon cast a special light over the forest. The clear,

brilliant rays and contrasting shadows create a primeval ambience. It is quiet except for that

special, calming sound of a light breeze through the leaves of the pine. In the distance you

can sometime hear a shepherd playing his pipe. In a personal sense, this is a balm in Gilead

for me!

Two species of Cistus are common in the pine forest, C. creticus and C. salvifolius. They are

easily distinguished by their flower color. The large pink flowers of C. creticus and the

slightly smaller but equally beautiful white flowers of C. salvifolius appear in May. On a hot

day, the fragrant resin of the plants is obvious. Upon closer examination, you can see the

numerous hairs that cover the leaves and young stems of both species. The resin will stick to

your hands if you collect leaves.

Cistus' resin is fragrant, as noted, and has been used for millennia to produce an incense.

Even today, the resin is collected in parts of Greece. It can be harvested in a variety of ways.

One ancient method is to comb the hair of goats who graze in plant communities where

Cistus is abundant. Another is by dragging a rake with long, leather tines across the shrubs

at the hottest time of day and then removing the resin when it is dry(3). To my knowledge, it

does not have any widespread use among modern Arabs.

Balm of Gilead http://web.odu.edu/webroot/instr/sci/plant.nsf/pages/cistus

3 of 8 29/11/2004 10:16 µµ

I have not found any local familiarity with the plants. When some Bedouin near Anjara were

asked the value of the plant, they simply replied that it was good forage for sheep and goats

indicating why the shrub is absent in heavily grazed areas.

The resin is also used for medicine, as a balm that can reduce inflammation of the skin.

Recent research on the biochemistry of the plant has shown the efficacy of compounds in

the plant for dermatological disorders(4).

Other resins extracted from plants in this type of Mediterranean community include mastic.

This is derived from the sap of at least two species of the genus Pistacia. The highest

quality comes from P. lentiscus on the Greek island of Chios. Such trees may have occurred

in Gilead in ancient times. However, there is no documentation for this. Another candidate

is the resin of the Aleppo pine which has been used as a pitch and gum. Use of the resin for

balm is unknown.

Back to Gilead. Is it possible these species of Cistus were widespread and more common

throughout Gilead and used as a medicine? Could this be the balm of Gilead? Again, the

weeping prophet in Jeremiah 46: 11: "Go up to Gilead and get balm, O virgin daughter of

Egypt. But you multiply remedies in vain; there is no healing for you." This implies that

Gilead was a special source of the medicine. If so, why was Gilead chosen as a site for

harvesting the balm rather than similar areas west of the Jordan? We simply don't know. Nor

should we neglect the possibility that the prophet Jeremiah was speaking in a metaphorically

way.

What is certain is that the beautiful Cistus shrubs, perhaps the most likely candidate for the

balm of Gilead, are much less frequent now then in previous years. This is due to the

widespread destruction of the forest type that harbors them. To ensure that future

generations of Jordanians can appreciate these attractive members of the indigenous flora,

they need to be protected. This can only be done by preserving the forest in which they

grow. Otherwise, there will be no balm in Gilead.

ENDNOTES

1. Adapted in part from Musselman, L. J. 2000. Jordan in Bloom.

2. Joshua 12:2.

3. Baumann, H. 1996. The Greek Plant World in Myth, Art and Literature. Translated by W. T. and E.

R. Stearn. Portland: Timber Press.

4. Baumann, H. 1996. The Greek Plant World in Myth, Art and Literature. Translated by W.

T. and E. R. Stearn. Portland: Timber Press. Danne, A., F. Peterett and A. Nahrstedt. 1993.

Proanthocyanidins from Cistus incanus. Phytochemistry 34(4): 1129-1133.

Rock rose

In my last lecture, I spoke at length about rockrose, or Balm of Gilead. Because it may be

Balm of Gilead http://web.odu.edu/webroot/instr/sci/plant.nsf/pages/cistus

4 of 8 29/11/2004 10:16 µµ

confused with some of the other plants used for balm, especially myrrh, I want to refer to it

again and draw upon some recent research.

Two species of Cistus are common in Syria, C. creticus and C. salvifolius. They are easily

distinguished by their flower color. The large pink flowers of C. creticus and the slightly

smaller but equally beautiful white flowers of C. salvifolius appear in May. On a hot day,

the fragrant resin of the plants is obvious. Upon closer examination, you can see the

numerous hairs that cover the leaves and young stems of both species. The resin will stick to

your hands if you collect leaves.

Cistus' resin is fragrant, as noted, and has been used for millennia to produce an incense.

Even today, the resin is collected in parts of Greece. It can be harvested in a variety of ways.

One ancient method is to comb the hair of goats who graze in plant communities where

Cistus is abundant. Another is by dragging a rake with long, leather tines across the shrubs

at the hottest time of day and then removing the resin when it is dry(1). To my knowledge, it

does not have any widespread use among modern Arabs.

The resin is also used for medicine, as a balm that can reduce inflammation of the skin.

Recent research on the biochemistry of the plant has shown the efficacy of compounds in

the plant for dermatological disorders(2). Recent research in Turkey shows that, of the seven

plants used as folk remedies for ulcers, the one with the greatest efficacy was C.

salvifolius(3).

Endnotes

1. Baumann, H. 1996. The Greek Plant World in Myth, Art and Literature. Translated by W.

T. and E. R. Stearn. Portland: Timber Press.

2. Danne, A., F. Peterett and A. Nahrstedt. 1993. Proanthocyanidins from Cistus incanus.

Phytochemistry 34(4): 1129-1133.

3. Yesilada E., I. Gurbuz, and H. Shibatajavascript: do_literal('AU=(Gurbuz I)');. 1999.

Screening of Turkish anti-ulcerogenic folk remedies for anti-Helicobacter pylori activity.

Journal of Ethnopharmacology 66(3):289-93. (The other plants were Spartium junceum,

cones of Cedrus libani, herbs and flowers of Centaurea solstitialis ssp. solstitialis, fruits of

Momordica charantia, herbaceous parts of Sambucus ebulus, and flowering herbs of

Hypericum perforatum.)

Balm of Gilead http://web.odu.edu/webroot/instr/sci/plant.nsf/pages/cistus

5 of 8 29/11/2004 10:16 µµ

Balm of Gilead http://web.odu.edu/webroot/instr/sci/plant.nsf/pages/cistus

6 of 8 29/11/2004 10:16 µµ

Balm of Gilead http://web.odu.edu/webroot/instr/sci/plant.nsf/pages/cistus

7 of 8 29/11/2004 10:16 µµ

Balm of Gilead http://web.odu.edu/webroot/instr/sci/plant.nsf/pages/cistus

8 of 8 29/11/2004 10:16 µµ

Cistus creticus subsp incanus - Cistaceae - Rock Rose

Arbuste à feuillage persistant

Floraison: Summer

Hauteur: 75cm

Guide de rusticité: 8 9

Germination: Expérience utile

Entretien: Entretien et soins nécessaires

Désignation: A charming evergreen shrub, quick to

flower from seed, often within 18 months. This older

variety was seen in gardens back in the 1700's. The

rich-pink blooms create a stunning carpet. Hardy in

the UK, Europe, Japan & Australia.

Of Mediterranean origin, the name Cistus is a

modified form of the Greek, kistos, while creticus is

a word which denotes that this particular species is

from Crete. Cistus belongs to the Rock Rose family,

a group which also includes Halimum,

Helianthemum and Halimocistus to name but a few.

Excellent ground cover as the plant naturally keeps

very low to the ground and the flowers are almost

stemless. Can also be used as miniature hedging or

at the front of cottage garden borders.

Semis: Sow February to July at 15-20C (59-68F) on

the surface of a good, free-draining compost, do not

cover seed. Place in a propagator or seal container

in a polythene bag until after germination which

usually takes 14-30 days. Do not exclude light at

any stage as this is beneficial to germination. It is

often beneficial to chip seed coat prior to sowing.

Culture: Pricking out (Transplanting): Cistus dislike

root disturbance so transplant as soon as large

enough to handle into 7.5cm (3in) pots. Grow on in

cool conditions. Planting out: When well grown,

gradually acclimatise to outdoor conditions before

planting out after all risk of frost, 45cm (18in) apart.

Prefers a poor but well drained soil in full sun. Can

tolerate winds, therefore a good maritime plant.

Entretien: Prune back any straggly growth on young

plants during March.

Catalogues Thompson et Morgande Graines et de plantes en lign

Bibliografia Cistus

http://www.inea.it/istflo/wkgrmedi/bibliocistus.htm#albidus

1 of 7 29/11/2004 10:05 µµ

GERMOPLASMA

MEDITERRANEO

Bibliografia

Cistus

(It.: Cisto ; En.: Rockrose)

C. monspeliensis

C. albidus

C. creticus ( = C. incanus

subsp. creticus)

C. incanus

C. ladanifer

C. monspeliensis

C. salviaefolius

C. salviaefolius C. 'Silver Pink'

C. albidus

Corral R., Perez-Garcia F., Pita J.M., 1989. Seed morphology and

histology in four species of Cistus L. (Cistaceae). Phytomorphology,

39 (1): 75-80.

Iriondo J.M., Moreno C., Perez C., 1995. Micropropagation of six

rockrose (Cistus) species. HortScience, 30 (5):.

Leduc J.P., Dexheimer J., Chevalier G., 1985. Etude ultrastructurale

comparee des associations de Terfezia leptoderma avec

Helianthemum salicifolium, Cistus albidus et Cistus salviaefolius.

Proceedings of the 1st European Symposium on Mycorrhizae, Dijon, 1-5

July 1985, 291-295.

Llusia J., Penuelas J., 2000. Seasonal patterns of terpene content and

emission from seven Mediterranean woody species in field

conditions. American journal of botany, 87 (1): 133-140.

Oliveira G., Penuelas J., 2001. Allocation of absorbed light energy into

photochemistry and dissipation in a semi-deciduous and an

evergreen Mediterranean woody species during winter. Australian

journal of plant physiology, 28 (6): 471-480.

Robles C., Garzino S., 1998. Essential oil composition of Cistus albidus

leaves. Phytochemistry, 48 (8):.

Sanchez-Blanco M.J., Rodriguez P., Morales M.A., Ortuno M.F., Torrecillas

A., 2002. Comparative growth and water relations of Cistus albidus

and Cistus monspeliensis plants during water deficit conditions and

recovery. Plant science, 162 (1): 107-113.

Bibliografia Cistus http://www.inea.it/istflo/wkgrmedi/bibliocistus.htm#albidus

2 of 7 29/11/2004 10:05 µµ

Vuillemin J., Bulard C., 1981. Ecophysiologie de la germination de

Cistus albidus L. et Cistus monspeliensis L..Naturalia

monspeliensia. Serie botanique, 46, 11 p.

C. creticus , C. incanus

Anastasaki T., Demetzos C., Perdetzoglou D., Gazouli M., Loukis A.,

Harvala C., 1999. Analysis of labdane-type diterpenes from

Cistus creticus (subsp. creticus and subsp. eriocephalus), by

GC and GC-MS. Planta medica, 65 (8): 735-739.

Aronne G., De Micco V., 2001. Seasonal dimorphism in the

Mediterranean Cistus incanus L. subsp. incanus. Annals of

botany, 87 (6): 789-794.

Berliner R., Jacoby B., Zamski E., 1986. Absence of Cistus incanus

from basaltic soils in Israel: effect of mycorrhizae. Ecology : a

publication of the Ecological Society of America, 67 (5):.

Berliner R., Jacoby B., Zamski E., 1987. Mycorrhiza is essential for

phosphate supply to Cistus incanus L. on native soils in

northern Israel. Journal of plant nutrition, 10 (9/16):.

Bjorn L.O., Callaghan T.V., Johnsen I., Lee J.A., Manetas Y., Paul N.D.,

Sonesson M., Welburn A.R., Coop D., Heide-Jorgensen, H.S., 1997.

The effects of UV-B radiation of European heathland species.

Plant ecology, 128 (1/2): 252-264.

Chinou I., Demetzos C., Harvala C., Roussakis C., Verbist J.F., 1994.

Cytotoxic and antibacterial labdane-type diterpenes from the

aerial parts of Cistus incanus subsp. creticus. Planta medica,.

Danne A., Petereit F., Nahrstedt A., 1993. Proanthocyanidins from

Cistus incanus. Phytochemistry, 34 (4):.

Demetzos C., Harvala C., Philianos S.M., Skaltsounis A.L., 1990. A

new labdane-type diterpene and other compounds from the

leaves of Cistus incanus ssp. creticus. Journal of natural products,

53 (5):1365-1368.

Demetzos C., Katerinopoulos H., Kouvarakis A., Stratigakis N., Loukis

A., Ekonomakis C., Spiliotis V., Tsaknis J., 1997. Composition and

antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of Cistus creticus

subsp. eriocephalus. Planta medica, 63 (2): 477-479.

Demetzos C., Loukis A., Spiliotis V., Zoakis N., Stratigakis N., 1995.

Composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of

Cistus creticus L. Journal of essential oil research, 7 (4): 407-410.

Demetzos C., Mitaku S., Couladis M., Havala C., Kokkinopoulos D.,

1994. Natural metabolites of ent-13-epi-manoyl oxide and other

cytotoxic diterpenes from the resin 'Ladano' of Cistus creticus.

Planta medica, 60 (6): 590-591.

Demetzos C., Mitaku S., Loukis A., Harvala C., Gally A., 1994. A new

drimane sesquiterpene, isomers of manoyl oxide and other

volatile constituents from the resin "Ladano" of Cistus incanus

subsp. creticus (L.) Heywood. Journal of essential oil research, 6

(1): 37-41.

Bibliografia Cistus http://www.inea.it/istflo/wkgrmedi/bibliocistus.htm#albidus

3 of 7 29/11/2004 10:05 µµ

Demetzos C., Mitaku S., Skaltsounis A.L., Harvala M.C.C., Libot F.,

1993. Diterpene esters of malonic acid from the resin 'Ladano' of

Cistus creticus. Phytochemistry35 (4): 979-981.

Demetzos C., Stahl B., Anastassaki T., Gazouli M., Tzouvelelis L.S.,

Rallis M., 1999. Chemical analysis and antimicrobial activity of

the resin Ladano, of its essential oils and of the isolated

compounds. Planta medica 65 (1): 76-78.

Fusconi A. , 1983. The development of the fungal sheath on Cistus

incanus short roots. Canadian journal of botany, 61 (10):.

Grammatikopoulos G. , 1999. Mechanisms for drought tolerance in

two Mediterranean seasonal dimorphic shrubs. Australian journal

of plant physiology, 26 (6): 587-593.

Gratani L., Bombelli A., 2000. Correlation between leaf age and other

leaf traits in three Mediterranean maquis shrub species:

Quercus ilex, Phillyrea latifolia and Cistus incanus.

Environmental and experimental botany, 43 (2): 141-153.

Hanley M.E., Fenner M., 1997. Seedling growth of four fire-following

Mediterranean plant species deprived of single mineral

nutrients. Functional ecology, 11 (3): 398-405.

Khazaal K.A., Parissi Z., Tsiouvaras C., Nastis A., Orskov E.R., 1996.

Assessment of phenolics-related antinutritive levels using the in

vitro gas production technique: a comparison between different

types of polyvinylpolypyrrolidone or polyethylene glycol. Journal

of the science of food and agriculture, 71 (4): 405-414.

Klocke J.A., Van Wagenen B., Balandrin M.F., 1986. The ellagitannin

geraniin and its hydrolysis products isolated as insect growth

inhibitors from semi-arid land plants. Phytochemistry, 25 (1):

85-91.

Kreimeyer J., Petereit F., Nahrstedt A., 1998. Separations of

flavan-3-ols and dimeric proanthocyanidins by capillary

electrophoresis. Planta medica, 64 (1): 63-67.

Manetas Y., Petropoulou Y., 2000. Nectar amount, pollinator visit

duration and pollination success in the Mediterranean shrub

Cistus creticus. Annals of botany, 86 (4): 815-820.

Papafotiou M., Triandaphyllou N., Chronopoulos J., 2000 Studies on

propagation of species of the xerophytic vegetation of Greece with

potential floricultural use. Acta Horticulture (ISHS) 541: 269-272.

Pela Z., Gerasopoulos D., Maloupa E., 2000. The effects of heat

pre-treatments and incubation temperature on germination of Cistus

creticus creticus seeds. Acta Horticulture (ISHS) 541: 365-372.

Pela Z., Pentcheva M., Gerasopoulos D., Maloupa E., 2000. In vitro

induction of adventitious roots and proliferation of Cistus creticus

creticus plants. Acta Horticulture (ISHS) 541: 317-322.

Peris J.B., Mateo G., Figuerola R., 1984. Sobre la presencia de

Cistus incanus L. en la Peninsula Iberica. Boletim da Sociedade

Broteriana, 57: 69-75.

Petereit F., Kolodziej H., Nahrstedt A., 1991. Flavan-3-ols and

proanthocyanidins from Cistus incanus. Phytochemistry 30 (3):

981-985.

Bibliografia Cistus http://www.inea.it/istflo/wkgrmedi/bibliocistus.htm#albidus

4 of 7 29/11/2004 10:05 µµ

Psaras G.K., Konsolaki M.J., 1986. The annual rhythm of cambial

activity in four subshrubs common in phryganic formations of

Greece. Israel journal of botany, 35 (1): 35-39.

Stephanous M., Manetas Y., 1997. The effects of seasons, exposure,

enhanced UV-B radiation, and water stress on leaf epicuticular

and internal UV-B absorbing capacity of Cistus creticus: a

Mediterranean field study. Journal of experimental botany, 48

(316):.

Stephanous M., Manetas Y., 1998. Enhanced UV-B radiation

increases the reproductive effort in the Mediterranean shrub

Cistus creticus under field conditions. Plant ecology, 134 (1):

91-96.

Stephanous M., Petropoulou Y., Georgiou O., Manetas Y., 2000.

Enhanced UV-B radiation, flower attributes and pollinator

behaviour in Cistus creticus: a Mediterranean field study. Plant

ecology, 47 (2): 165-171.

Sternberg M., Shoshany M., 2001. Aboveground biomass allocation

and water content relationships in Mediterranean trees and

shrubs in two climatological regions in Israel. Plant ecology, 157

(2): 173-181.

Thanos C.A., Georghiou K., 1988. Ecophysiology of fire-stimulated

seed germination in Cistus incanus ssp. creticus (L.) Heywood

and C. salvifolius. Plant, cell and environment, 11 (9):841-849.

Troumbis A.Y. , 1996. Seed persistence versus soil seed bank

persistence: the case of the post-fire seeder Cistus incanus L.

Écoscience 3 (4): 461-468.

Vardavakis E., 1988. Seasonal fluctuation of non-parasitic

mycoflora associated with living leaves of Cistus incanus,

Arbutus unedo and Quercus coccifera. Mycologia, 80 (2):

200-210.

C. ladanifer

Acosta F.J., Delgado J.A., Lopez F., Serrano J.M., 1997. Functional

features and ontogenic changes in reproductive allocation and

partitioning strategies of plant modules. Plant ecology, 132 (1):

71-76.

Alados C.L., Navarro T., Cabezudo B., 1999. Tolerance assessment

of Cistus ladanifer to serpentine soils by developmental stability

analysis. Plant ecology, 143 (1): 51-66.

Chaves N., Escudero J.C., Gutierrez-Merino C., 1993. Seasonal

variation of exudate of Cistus ladanifer. Journal of chemical

ecology, 19 (11):.

Chaves N., Escudero J.C., Gutierrez-Merino C., 1997. Quantitative

variation of flavonoids among individuals of a Cistus ladanifer

population. Biochemical systematics and ecology, 25 (5): 429-435.

Chaves N., Escudero J.C., Gutierrez-Merino C., 1997. Role of

ecological variables in the seasonal variation of flavonoid

content of Cistus ladanifer exudate. Journal of agricultural and

food chemistry, 45 (10): 579-603.

Bibliografia Cistus http://www.inea.it/istflo/wkgrmedi/bibliocistus.htm#albidus

5 of 7 29/11/2004 10:05 µµ

Chaves N., Escudero J.C., 1997. Allelopathic effect of Cistus

ladanifer on seed germination. Functional ecology, 11 (4): 432-440.

Chaves N. Rios J.J., Gutierrez C., Escudero J.C., Olias J.M., 1998.

Analysis of secreted flavonoids of Cistus ladanifer L. by

high-performance liquid chromatography-particle beam mass

spectrometry. Journal of chromatography, 799 (1/2): 111-115.

Corral R., Perez-Garcia F. Pita, J.M., 1989. Seed morphology and

histology in four species of Cistus L. (Cistaceae).

Phytomorphology., 39 (1): 75-80.

Delgado J.A., Serrano J.M., Lopez F., Acosta F.J., 2001.Heat shock,

mass-dependent germination, and seed yield as related

components of fitness in Cistus ladanifer. Environmental and

experimental botany, 46 (1): 11-20.

Dominguez M.T., 1994. Influence of polyphenols in the litter

decomposition of autochthonous (Quercus ilex L, Quercus

suber L, Pinus pinea L, Cistus ladanifer L, and Halimium

Halimifolium W.K.) and introduced species (Eucalyptus globulus

L. and Eucalyptus camaldulensis D.) in the southwest of Spain.

Acta Horticulturae 381, 425-428.

Ferrandis P., Herranz J.M., Martinez-Sanchez J.J., 1999. Effect of fire

on hard-coated Cistaceae seed banks and its influence on

techniques for quantifying seed banks. Plant ecology, 144 (1):

103-114.

Guy I., Vernin G., 1996. Minor compounds from Cistus ladaniferus

L. essential oil from Esterel. 2. Acids and phenols. Journal of

essential oil research, 8 (4): 455-462.

Iriondo J.M., Moreno C., Perez C., 1995. Micropropagation of six

rockrose (Cistus) species.HortScience, 30 (5):.

Lansac A.R., Martin A., Roldan A., 1995. Mycorrhizal colonization

and drought interactions of Mediterranean shrubs under

greenhouse conditions. Arid soil research and rehabilitation, 9 (2):

167-175.

Nunez-Olivera E., Martinez-Abaigar J., Escudero J.C., 1996.

Adaptability of leaves of Cistus ladanifer to widely varying

environmental conditions. Functional ecology, 10 (5): 636-646.

Paton D., Azocar P., Tovar J., 1998. Growth and productivity in

forage biomass in relation to the age assessed by

dendrochronology in the evergreen shrub Cistus ladanifer (L.)

using different regression models. Journal of arid environments,

38 (2): 221-235.

Pereira I.P., Dias A.S., Dias L.S., 1993. Effects of heat treatments on

the germination of Cistus landanifer L. Acta Horticulturae 344:

229-237.

Perez-Garcia F., 1997. Germination of Cistus ladanifer seeds in

relation to parent material. Plant ecology, 133 (1): 57-62.

Proksch P., Gulz P.G., Budzikiewicz H., 1980. Further oxygenated

compounds in the essential oil of Cistus ladanifer L. (Cistaceae).

Zeitschrift fur Naturforschung. Section C: Biosciences, 35 (7/8):

529-532

Bibliografia Cistus http://www.inea.it/istflo/wkgrmedi/bibliocistus.htm#albidus

6 of 7 29/11/2004 10:05 µµ

Proksch P., Gulz P.G., Budzikiewicz H., 1980. Phenylpropanoic acid

esters in the essential oil of Cistus ladanifer L. (Cistaceae).

Zeitschrift fur Naturforschung. Section C: Biosciences, 35 (3/4):

201-203.

Talavera S., Gibbs P.E., Herrera J., 1993. Reproductive biology of

Cistus ladanifer (Cistaceae). Plant systematics and evolution, 186

(3/4): 123-134.

Tomas-Lorente F., Garcia-Grau M.M., Nieto J.L., Tomas-Barberan F.A.,

1992. Flavonoids from Cistus ladanifer bee pollen.

Phytochemistry, 31 (6):.

C. monspeliensis

Angelopoulou D., Demetzos C., Dimas C., Perdetzoglou D., Loukis A. ,

2001. Essential oils and hexane extracts from leaves and fruits

of Cistus monspeliensis. Cytotoxic activity of ent-13-epi-manoyl

oxide and its isomers. Planta medica,67 (2): 168-171.

Angelopoulou D., Demetzos C., Perdetzoglou D., 2002. Diurnal and

seasonal variation of the essential oil labdanes and clerodanes

from Cistus monspeliensis L. leaves. Biochemical systematics and

ecology, 30 (3): 189-203.

Ascenao L., Pais M.S.S., 1981. Ultrastructural aspects of secretory

trichromes in Cistus monspeliensis. Tasks for vegetation science,

4, 27-38.

Cavero I., Livi O., 1970. Estrazione, frazionamento ed esame dei

costituenti del Cistus monspeliensis L. Ann. Chim., 60 (7):

469-482.

Demetzos C., Dimas K., Hatziantoniou S., Anastasaki T., Angelopoulou

D. , 2001. Cytotoxic and anti-inflammatory activity of labdane

and cis-clerodane type diterpenes. Planta medica, 67 (7): 614-618.

Glyphis J.P., Puttick G.M., 1989. Phenolics, nutrition and insect

herbivory in some garrigue and maquis plant species. Oecologia,

78 (2): 259-263.

Ibrahima A., Joffre R., Gillon D., 1995. Changes in litter during the

initial leaching phase: an experiment on the leaf litter of

Mediterranean species. Soil biology & biochemistry, 27 (7):

931-939.

Roble C., Garzino S., 2000. Infraspecific variability in the essential

oil composition of Cistus monspeliensis leaves. Phytochemistry,

53 (1): 71-75.

Sanchez-Blanco M.J., Rodriguez P., Morales M.A., Ortuno M.F.,

Torrecillas A., 2002. Comparative growth and water relations of

Cistus albidus and Cistus monspeliensis plants during water

deficit conditions and recovery. Plant science (Shannon, Ireland),

162 (1):107-113.

Vuillemin J., Bulard C., 1981. Ecophysiologie de la germination de

Cistus albidus L. et Cistus monspeliensis L. .Naturalia

monspeliensia. Serie botanique, 46, 11 p.

C. salviaefolius

Bibliografia Cistus http://www.inea.it/istflo/wkgrmedi/bibliocistus.htm#albidus

7 of 7 29/11/2004 10:05 µµ

Leduc J.P., Dexheimer J., Chevalier G., 1985. Etude ultrastructurale

comparee des associations de Terfezia leptoderma avec

Helianthemum salicifolium, Cistus albidus et Cistus

salviaefolius. Proceedings of the 1st European Symposium on

Mycorrhizae, Dijon, 1-5 July 1985, 291-295.

Ulteriore bibliografia

Inizio pagina

Home page Gruppo di Lavoro "Germoplasma Mediterraneo"

Home page